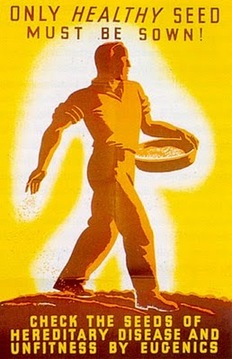

However, when you read our critiques of SLP, you’ll notice that the majority of what we’ve discussed has been focused much less on the role of individual pathologists, and much more on the discipline, teachings, and premises of Speech-Language Pathology as a whole.

This is because while it’s true that not all SLPs do all of the things that DIS has critiqued, the much more important point is that every person who stutters still experiences the harmful effects of SLP as a whole. Our society has taken the discipline and industry of SLP as the default way of understanding and responding to stuttering, and the things it says about stuttering affect every single one of us, whether we’ve ever set foot in a SLP’s office or not.

Every day I encounter the assumption that my stutter is a problem to be treated and coped with. This assumption is reinforced by the practices, research, and very existence of the SLP industry. In diagnosing stuttering as a medical condition and looking for ways to treat and rehabilitate stutterers, SLP is creating and reinforcing the backdrop of discrimination (and assimilation) against which I live every day of my life.

Of course the vast majority of us who have been to speech therapy have experience this outright—the assumption that it is my speech (not the biases of my listeners) which causes my difficulty in communicating. The assumption that the underlying social struggles I face (anxiety, fear, shyness, low self-esteem) are best addressed by modifying me or my speech rather than ableism within society.

Moreover, these exact opinions are replicated by society as a whole. For one thing, everyone constantly assumes that if I’m not receiving speech therapy I should be. For another, everyone thinks of my stutter as a struggle to overcome—a deficiency to be disliked and minimized. These biases against my speech are backed up and made credible by SLP.

At Did I Stutter, we are instead claiming that there is quite literally nothing wrong with stuttering. We want to be proud of our stutters. We want completely to undo the assumptions we hear every day that there is something unfortunate or deficient about our speech and that our voices would be better off modified or changed. We want to go to schools and workplaces where those around us don’t wish we were fluent and don’t expect us to wish it too. We want to understand the “impediments” in our speech as having nothing to do with our physical bodies and everything to do with a society that doesn’t accommodate our voices just as they are. For better or worse, these goals stand in opposition to Speech-Language Pathology.

It is for this reason that Did I Stutter has been careful to position itself outside the field and logic of SLP. In doing so we aren’t critiquing the intentions of individual SLPs, who are by and large in the field to help people. Rather, we are resisting the industry’s entire assumption that disability should be responded to in therapeutic ways. Like many other liberation movements, we want to make room for people with speech impediments to define their voices for themselves without needing to defer to “experts.” We also recognize that SLPs face an unfortunate conflict of interest as it does not economically benefit SLPs or the industry as a whole for stutterers to embrace their voices just as they are and stop seeking therapeutic intervention. This is part of why we are grateful for the work of those SLPs who do resist the ableism of the larger industry, yet part of why we know that resistance from inside an ableist system will never be enough.

It may be true that not all speech-language pathologists reinforce the ableism of Speech-Language Pathology.

But yes, all stutterers are damaged by it.

-Josh and Charis

RSS Feed

RSS Feed