From a young age I’ve had a strong sense of social justice and the principles of respect and value for each individual have been highly important to me. Feeling disrespected or seeing others be disrespectful has always made me angry. Fast-forward to my final year of postgraduate training to become a speech and language therapist here in the UK, when a tutor recommended a book that had just been published: ‘Mustn’t Grumble’ (Keith, 1994) - a controversial collection of short stories and poems reflecting the varied facets of disabled women’s experience. How little did I know that it would challenge everything I was learning to the core.

Through this text, I uncovered a deep connection with the radical ideas underpinning the disabled people’s movement. The clearly articulated and angry stories of oppression and exclusion taught me that, from a social model perspective, people aren’t disabled because they have an impaired body, mind or means of communication, but because society places structural, environmental and attitudinal barriers in their way. Viewing disability as a civil rights and justice issue rather than a medical or therapeutic one resonated deeply - there was something refreshing, raw and alive about the social model and its open invitation to engage in a dialogue about difference that extended beyond the focus of loss and adjustment. However, it represented a direct challenge to the influential medical model, which has traditionally shaped the institutions within which speech and language therapists are trained and generally work in the UK and which perpetuates the historical focus on ‘deficit’ and the need for ‘therapeutic intervention’ by ‘trained, expert practitioners’. As a therapist-in-training, it was unsettling to discover the extent to which the social model contested the fundamental principles upon which therapy is based (Finkelstein, 1993; Oliver, 1993). Furthermore, as much therapeutic practice has traditionally focused on ‘normalisation’ and the ‘reduction or eradication of difference’, the social model revealed an intrinsic paradox; that the narrow focus of restoration therapy can only serve to reinforce and reaffirm social norms and stigma rather than acting as a vehicle through which these prevailing norms can be challenged and renegotiated (Oliver, 1996).

As a speech and language therapist I’ve always worked in both the fields of stammering and brain injury. I believe my approach to therapy has benefited greatly from the cross-fertilisation of different ideas, theories and practices within these two fields. I was fortunate from early in my career to have ready access to forward-thinking therapists committed to engaging with the social model more actively (Parr et al., 1997; Pound et al., 2000; Parr et al, 2003; Felson Duchan & Byng, 2004). Through their pioneering work, many people with aphasia have been given a voice and role in defining the lived experience of aphasia and evaluating therapy services here in the UK. This has prompted a call for the focus of therapy to broaden and address the role that self-identity, society and social stigma play in making the processes of living with aphasia more challenging.

In contrast, I’ve been intrigued by how slowly the social model has been embraced within the stammering community. Indeed, the powerful influence of the medical model is still very apparent – as demonstrated by the growing interest in the neuroanatomical basis of stammering and fluency shaping approaches for young children that currently dominate conference programmes. However, in the spirit of client autonomy and choice, no matter how dominant, the medical model is only one lens through which stammering and stammering therapy can be viewed. The social model clearly illustrates how prevailing norms, language and stereotypes can go unchallenged, become internalised and, therefore, self-oppressive. This is of particular relevance to stammering and enables us to re-consider and re-define where the ‘problem’ of stammering is located.

I’m delighted to see a growing number of people who stammer engaging directly with the disability activist movement: The Did I Stutter? Project, members of the British Stammering Association and the Employers Stammering Network (ESN) to name but a few. Also, that stammering therapists are starting to engage in these conversations too (e.g. Michael Boyle, Chris Constantino). Positioning the stammering therapy discourse within the broader disability discourse offers a means of revising and extending the boundaries of thinking about stammering and stammering therapy.

So what might this mean for stammering therapists? Naturally, I can only speak from personal experience. The following is a reflection on how engagement with the social model has enriched and informed my philosophy of therapy and how I embody theory in practice.

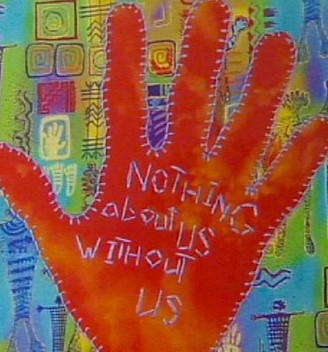

The social model has encouraged me to embrace ideas that promote thinking against the grain. It’s pushed me to critically examine my attitudes, beliefs and assumptions about otherness, difference and disability and how these have been shaped over time. This in turn has challenged me to actively reflect on and question my personal motives for the work that I do and to articulate my philosophy of therapy more clearly and transparently with clients. For me, stammering therapy is about reducing social- and self-oppression through the recognition, removal or negotiation of structural, physical and attitudinal barriers in order for people to live choice-fully and stammer openly, confidently and without shame.

To this end, the social model has taught me the importance of transforming social relationships and power dynamics, which involves being willing to get out of the therapy room and into the real world context. I’m currently involved in co-developing and -facilitating a corporate training programme in conjunction with a business leader from the Employers Stammering Network (ESN) and therapists from City Lit. The ESN is an organised initiative, which together with the British Stammering Association, is working to change society’s understanding of and attitudes towards stammering in the UK workplace. Following the success of a pilot project last year, we are now rolling out a more extensive programme of workshops for employees who stammer, managers and HR departments. Watch this space!

The social model has taught me the power of language and to be mindful of how I talk about and frame stammering. I consistently avoid using binary oppositions (e.g. ‘good’/’bad’) that place stammering on the negative pole and reinforce fluency as the gold standard in an on-going commitment to not reinforce ableism. I also avoid framing stammering as ‘a defect’, ‘impediment’ or ‘disorder’ and openly question others’ use of such language. In addition, the social model has taught me to respect personal language preferences in others (e.g. person-first or identity-first language, such as ‘person who stammers’ or ‘stammerer’), the political stance that language of identity can represent and the perils of unquestioningly applying a broad linguistic standard (e.g. PWS).

Engaging clients in conversations about the contrasting ways difference is understood in society and the different ways stammering can therefore be defined is central to my approach to therapy. I frequently witness how liberating an understanding of the social model can be as it shifts the focus away from ‘what is wrong with me’ to critically examining ‘what is wrong with the broader system in which I live’. Being explicit and transparent about my philosophy of therapy also enables clients to make more informed decisions about what they feel might be helpful at a particular point of time. There is no ‘one size fits all’ in stammering therapy, so offering a range of approaches and recognising that people’s therapy preferences change over time affords greater client autonomy. I balance idealism with realism; whilst the growing number of radical stammering communities are re-visioning stammering and the future, it will inevitably take time for this important work to impact the day-to-day reality for everyone who stammers. Therapy, therefore, involves the delicate balancing act of offering access to these radical communities and their vision whilst also working from where people are at. That said, the social model has also taught me greater humility, an appreciation that many people live well with stammering outside of therapy and to therefore not view the need for therapy as automatic.

I have found that introducing people to Michael Boyle’s research into stigma and self-stigma as well as the concept of internalised oppression offers a different way of bringing about changes in attitude. Additionally, introducing people to stammering activism and dysfluency pride offers people an opportunity to explore and discover new identities and communities. Social media is a powerful mechanism for bringing people together, so I try to stay current and signpost diverse resources and communities via Twitter and Facebook. Additionally, in keeping with the belief that the ‘personal can become political’ I regularly encourage people to blog, vlog, write articles, get involved in student and therapist training as well as co-presenting at conferences. A number of clients have since gone on to campaign more actively through organised public speaking events, the production of documentaries and the creation of peer groups and other political platforms for people to join together as a collective and challenge prevailing negative attitudes and misconceptions about stammering.

I’m so very grateful that a book recommendation opened my eyes to the social model and the disabled people’s movement so early in my career. It has affirmed the importance of staying open to a plurality of ideas and theories as well as the value of exploring views that deviate from conventional thought and practice. While this has resulted in a career path that hasn’t always been straightforward to navigate, it’s undoubtedly shaped a path that has been more colourful, creative and enriching as a result.

Returning to the therapist I overheard at the international stammering conference… to me, what remains so deeply insidious in their query is what has not yet been questioned and what, therefore, remains out of awareness and unexamined. This strikes me as perilous not only for the individual therapist concerned, but, if representative of the majority, for stammering therapy and the stammering community at large.

-Sam Simpson

References:

Felson Duchan J. & Byng S. (2004). Challenging Aphasia Therapies: Broadening the Discourse and Extending the Boundaries. Psychology Press, New York.

Finkelstein V. (1993) Disability: a social challenge or an administrative responsibility? In Swain J., Finkelstein V., French S. & Oliver M. (eds) Disabling Barriers – Enabling Environments. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Keith L. (1994). Mustn’t Grumble: Writing by Disabled Women. The Women’s Press, London.

Oliver M. (1993) Disability and dependency: a creation of industrial societies? In Swain J., Finkelstein V., French S. & Oliver M. (eds) Disabling Barriers – Enabling Environments. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Oliver M. (1996). A sociology of disability or a disablist sociology? In Barton L. (ed) Disability and Society: Emerging Issues and Insights. Longman, London

Parr S., Byng S. & Gilpin S. with Ireland C. (1997) Talking about Aphasia. Open University Press, Berkshire.

Pound C., Parr, S., Lindsay J. & Woolf C. (2000). Beyond Aphasia: Therapies for Living with Communication Disability. Winslow Press Ltd., Oxon.

Parr S., Duchan J. & Pound C. (2003). Aphasia Inside Out: Reflections on Communication Disability. Open University Press, Berkshire.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed