Today, I would like to talk about a recent article published by the International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology titled “To be or not to be: Stuttering and the human costs of being ‘un-disabled’.” The essay is written by Brian Paul Watermeyer (PhD), a clinical psychologist at the Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at Cape Town University, and Harsha Kathard (D.Ed), an SLP professor at Cape Town University.

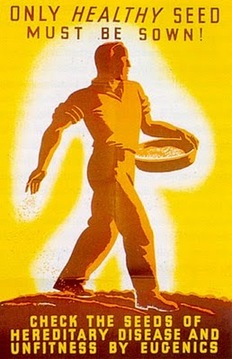

The central argument of this paper is that there is a psychological cost in striving for normalcy, and that SLPs are often complicit in creating the desire to be normal within stutterers. As Watermeyer and Kathard write, “[W]e hope that these reflections may contribute to deepening reflection among rehabilitation professionals of how our work may harmonize unhelpfully with cultural imperatives towards normalcy” (p. 8). This is a bold and important question, and I hope that it continues to be asked.

Watermeyer and Kathard explicitly offer few answers. Rather, their hope in this piece is to open up space for future research. One of the questions they return to often is why, given that many other disabilities have been claimed as a positive part of one’s identity, is it seemingly so hard to think of stuttering as a “legitimate way of being and communicating” (p. 6)? Why is it that “the idea of making space for stuttering as a legitimate human difference—like some other impairments—feels incongruous?” (p. 6) Again, this is an excellent question meant to break down obstacles to (what we would refer to as) stuttering pride.

However, one of the peculiar things about this paper is that while explicitly written from the perspective of disability studies, it doesn’t draw very deeply upon the resources offered by the field. Besides a couple one-off references to Garland-Thomson (1997, 2009) and Davis (1996), Watermeyer and Kathard draw almost exclusively upon Watermeyer’s previous publications. This of course wouldn’t be a problem if there was a lack of relevant literature to work with and if Watermeyer offered the best theory with which to think critically about stuttering. Yet I am not convinced that this is the case. I suggest the result is that Watermeyer and Kathard 1) have difficulty drawing generative conclusions and 2) are at times forced to create problems and distinctions that don’t actually exist.

For example, Watermeyer and Kathard argue that most disabilities can be incorporated as a positive aspect of identity because “all ‘selves’ are both normal and not, both frail and robust and subject to both hope and despair” (p. 6). Yet Watermeyer and Kathard continue by setting stuttering in a separate category: “In contrast, data on stuttering suggest a picture of discrete, competing selves jostling for prominence. Here, to stutter is to fail in the quest to embody the ‘normal’ part of the inner split” (p. 6). This is a rather arbitrary and unhelpful distinction for a host of reasons. The first one that comes to mind is that Watermeyer and Kathard tend to treat identity as a free-floating thing in the social sphere. Rather than drawing conclusions about stuttering from generalized notions of identity, we need to investigate the (historical) process of how specific arrangements of identity and subjectivity are formed around the experience of stuttering. Of course the experience of stuttering is both similar and different from other forms of disability. Yet this in itself means very little.

The larger problem, however, is that these are not primarily academic issues. If true that it is more difficult for society in general to think of stuttering as a “legitimate way of being and communicating” (p. 6) than using a wheelchair, for example, this is only because activists in the disability rights movement have been working tirelessly for 40 years to change ableist perceptions and institutions/structures around what it means to use/require a wheelchair. Stuttering, on the other hand, does not have this history. This is an activist and social issue, not an inherent problem with “stuttering identity.”

In conclusion, and on a related note, it is telling the way in which this article ends. Following their excellent call for greater reflection on how SLP practices may be complicit with cultural imperatives towards normalcy, Watermeyer and Kathard write: “Integrating this awareness into new theoretical approaches may create a more humanitarian balance between the drive to correct and the path towards societies more able to manage difference” (p. 8). I find it very telling that the outcome of reflecting on our culture’s drive toward normalcy is summed up in words like “balance” and “manage difference.” Understanding disability/stuttering justice as a “balance” or middle ground between assimilating difference and making space for it will always be the problem of working within the system, of trying to produce change from within the medical-industrial complex. Similarly, difference is not described as something to embrace, celebrate, or radically include, but as something (a challenge or problem) for a bureaucracy to “manage.” Managing difference is not how a more just world is created. In this context, it is hard to take seriously their concluding belief that “social change in disability is not the sole responsibility of health professions, but our influence in shaping disability culture is beyond question” (p. 8).

Excuse us, but we are not done with the questions.

-Josh

RSS Feed

RSS Feed