Yet one would hardly need to believe the US government is hiding aliens in Area 51 to notice, mimicking the melodramatic language of politicians, a “war on disability.” Put more soberly, there is an intensive and sustained global effort to irradiate disability from the human population, an effort rooted in the common belief that disability is a tragedy—causing pain, suffering, disadvantage—and the world would be a better place without it.

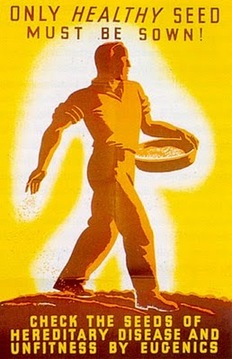

While society has always discriminated against disabiity to some degree, it is only in the past 150 years that humans have believed themselves capable of removing disability from the human population altogether in the happy march of human progress. The irradiation of disability fits into a larger story, into the history of what is termed “eugenics.”

Eugenics is the attempt to improve the genetic stock of humanity—literally to create better people. Originating in the mid-nineteenth century with Francis Galton, an English scientist responsible for discovering statistical techniques of measuring heritable human abilities and characteristics, eugenics caught on like wildfire across Europe and especially in North America. Galton introduced the idea of statistically “normal” human traits and the idea that the quality of the human race could be improved by promoting the reproduction of “higher” quality people (positive eugenics) while discouraging the reproduction of “lower” quality people (negative eugenics).

Following from Galton’s theory of negative eugenics, institutions were quickly erected to separate those deemed “feeble-minded” from the rest of society. Built upon some very sketchy science, thousands of disabled people (or people diagnosed as disabled) were segregated and sterilized in an attempt to produce a better population, or a better human “stock” throughout Canada and the US. In Alberta, the Canadian province in which I live, 2 800 people were approved by the government between 1928 and 1972 to be sterilized non-consensually and often without their knowledge (I am involved with a major research project called the Living Archives on Eugenics in Western Canada) .

The logic of eugenics—that the human race should and can be improved—is most infamously associated with the Nazi Final Solution. Yet it is less-well known that the creation of a “pure” Aryan race was first tested on disabled people. By the end of WW2, an estimated 275 000 disabled people had been murdered by the Nazis, many of them severely intellectually disabled or mentally ill.[1] Moreover, it is worth noting that many champions of eugenics in North America praised early Nazi attempts at social hygiene. These events seem chilling from our perspective, yet eliminating "less suitable" kinds of people through eugenics was commonly assumed as necessary to combat poverty, crime, and a host of racist and ableist cultural anxieties.

How could this happen?

Put in simple terms, the ableism propelling eugenics was never slowed. While no one in the scientific community now suggests that certain racialized groups are inferior and should not exist, the idea that the world would be a better place without disability is rarely questioned. Disabled people are still treated as less-than fully human. Think of the language we commonly use to describe unwanted things: “that’s so lame” “are you blind?” “what a dumb idea” “you’re so insane” (there are many other ableist terms that get thrown around). What is disability in movies but a tragedy, an inspiration, or something to laugh at? How many times have you heard someone exclaim that they would rather die than be blind or in a wheelchair? Disabled lives are still not understood as fully human.

The ugly eugenics of the 20th century is now being replaced by shiny “newgenic” practices such as pre-natal screening that still attempt to stop disabled people from existing. The methods have changed, but the endgame is the same: a world without disability, weakness, and deviance. In other words, while we decry sterilization and (sometimes) institutionalization as inhumane, eugenic beliefs are only gaining steam.

It is from this perspective that I worry about the search for a stuttering cure. There was much hubbub about a “stuttering gene” a little while back, a search that would not have been out of place 100 years ago. I have sat across from speech-language pathologists excitedly telling me about the search for a stuttering cure and wondered: what other reason is there to find a cure for stuttering than to eliminate our voices and to remove stuttering from the gene pool and the human condition?

Being from Alberta and knowing about our shameful eugenic history colours the search for a stuttering cure for me. As well intentioned as it may seem, a “cure” for stuttering cannot be separated from the idea and practise of eugenics that assumes the world would be a better place without disability, without us. We already screen for Down Syndrome since we have decided some lives are more valuable than others. In 20 years might we screen foetuses for stuttering? (I am, by the way, dubious that a stuttering gene will ever be found). What about Speech Easy? Pharmaceuticals? Therapy? While often advertised as helping us “find our voice,” I believe these practices are often eugenic, aimed at normalization. It is just assumed that, given a choice, we would rather talk fluently. We would rather not be disabled.

I do not believe that the world would be a better place without disability and without stuttering. We have seen shadows of that world and it is foul and dangerous, full of fear and hate. Rather, with disability theorist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson,[2] I believe we need to understand disability as intrinsic to our humanity, something that needs to be “conserved” and encouraged to flourish in the face of eugenic ideas and practises. My desire is for a world where different types of bodies, voices, minds, experiences, and people can exist together, learn from each other, and yes, even love each other.

-Josh

[1] Braddock, David L. and Susan L Parish, 2001, “An Institutional History of Disability,” in (ed.) Gary L. Albrecht, Katherine D. Seelman, and Michael Bury, Handbook of Disability Studies (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 40.

[2] Garland-Thompson, Rosemarie, 2012, “The Case for Conserving Disability,” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 9 (3): 339-55.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed